Rip Currents SLS Beachsafe

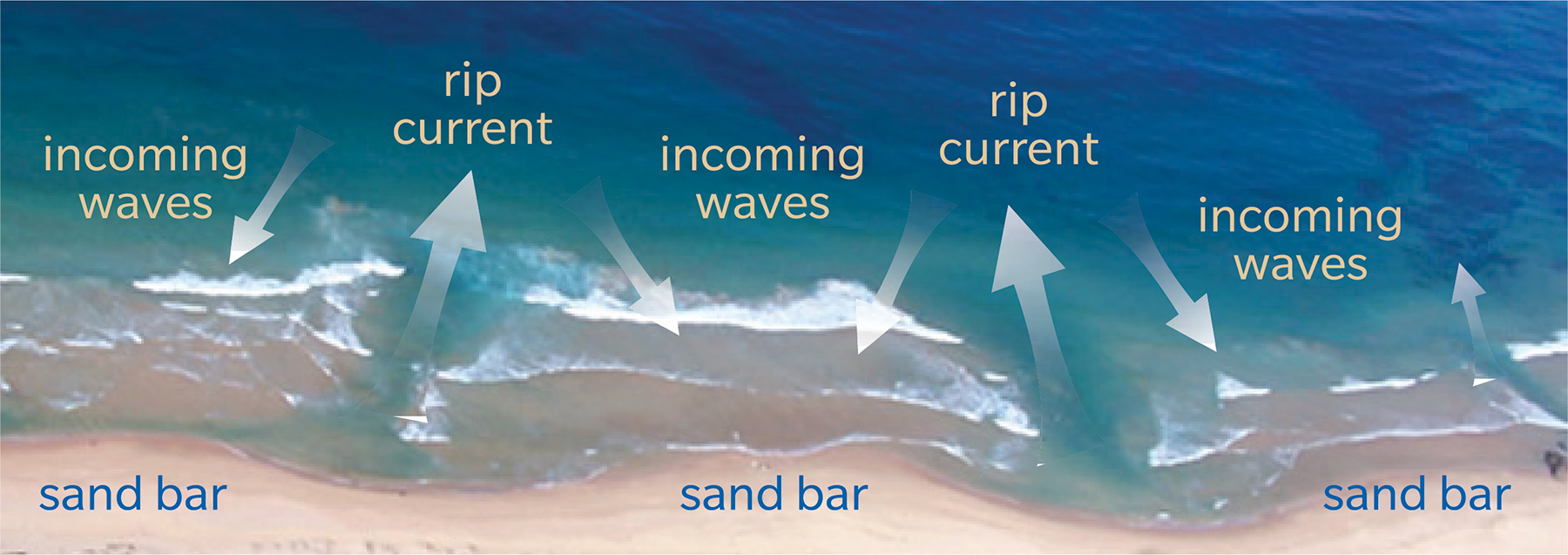

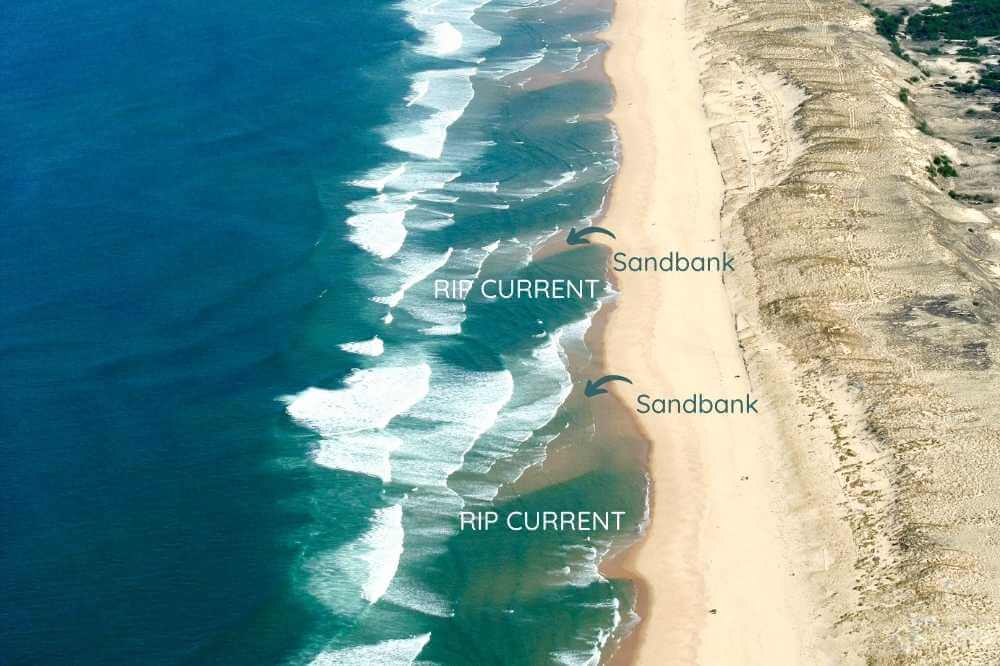

Rip currents are channelized currents of water flowing away from shore at surf beaches. Rip currents typically form at breaks in sandbars, and also near structures such as jetties and piers. Rip currents are commonly found on all surf beaches, including Great Lakes beaches. Why are rip currents dangerous? Rip currents pull people away from shore.

Rip Current Monitor

Rip currents are fast, concentrated flows of water that can form on beaches that have breaking waves. 1 Every beach is different, but rips generally form when waves are breaking and the underwater surface is uneven (e.g., if there are sandbars, piers, jetties, or groins along the beach). Worldwide, hundreds of people drown in rip currents each.

Rip currents are a natural hazard along coasts here's how to spot them

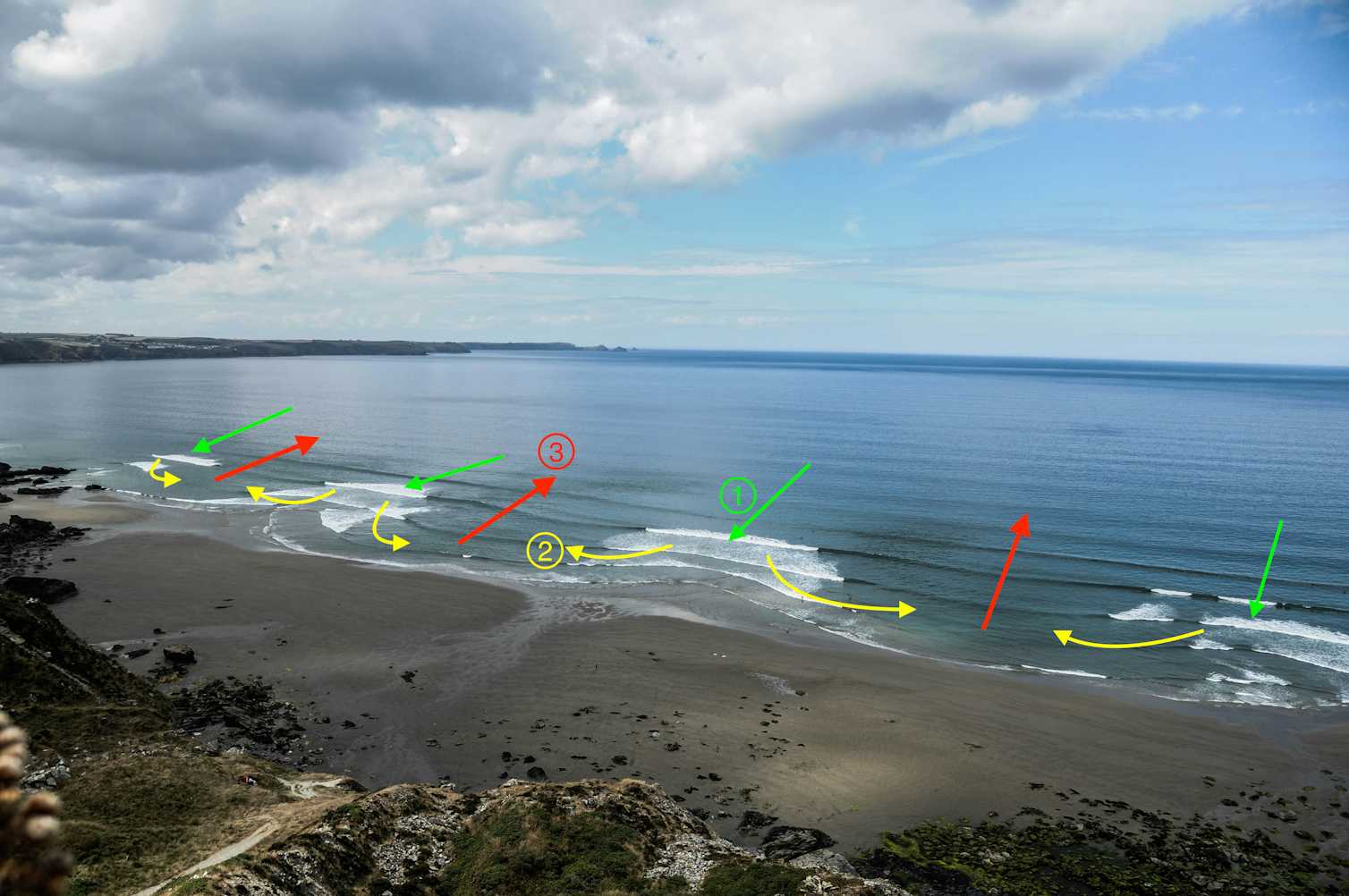

The traditional and widely accepted view of rip current circulation regime and rip current system structure (Fig. 3 a) is based on early Lagrangian studies and observations by Shepard et al. (1941) and Shepard and Inman (1950) and describes nearshore circulation involving rip currents and the continuous interchange of water between the surf zone and areas offshore (Inman and Brush, 1973).

Riptide a maritime phenomenon to understand for a leisurely swim

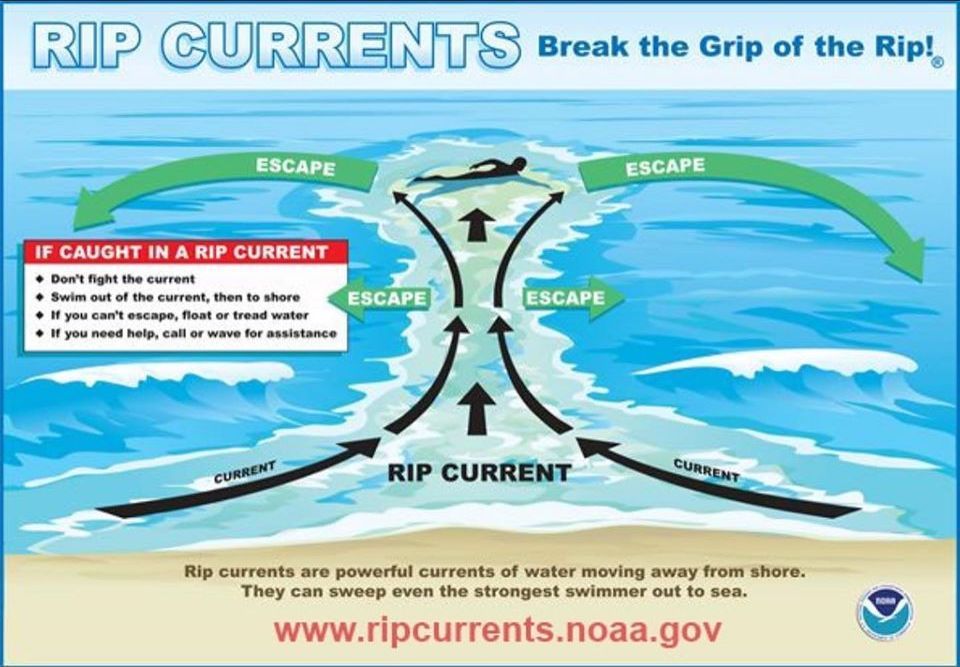

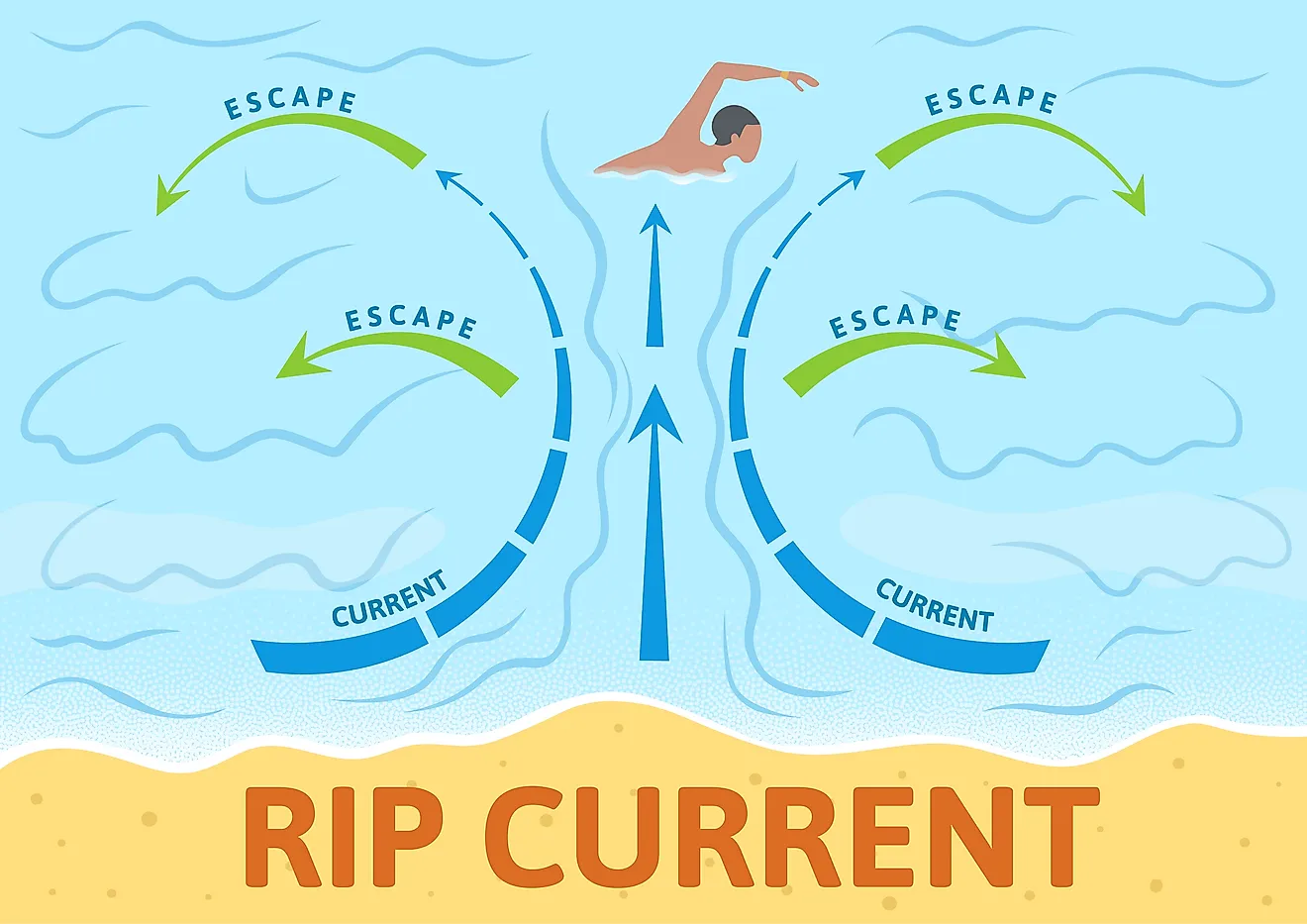

Relax, rip currents don't pull you under. Don't swim against the current. You may be able to escape by swimming out of the current in a direction following the shoreline, or toward breaking waves, then at an angle toward the beach. You may be able to escape by floating or treading water if the current circulates back toward shore.

Video of rip current Britannica

Rip currents are strong, narrow channels of fast-moving water that can pose a danger to swimmers and surfers alike. In this section, we will explore the formation and development of rip currents, as well as the different types of rip currents commonly encountered. Formation and Development

PSA Rip Currents Can Kill Homeless Voice

For the first time, NOAA is launching a national rip current forecast model, aimed at saving lives of beach-goers around the country. This new model can predict the hourly probability of rip currents along U.S. beaches up to six days out. NOAA's National Ocean Service and National Weather Service collaboratively developed and implemented the.

Rip currents are a major surf zone hazard Beaches.ie Beaches.ie

Here we are going to explain what rip currents are and how to act if you are surprised by one. This is how rip currents are formed. The intensity of the waves and the topographic shape of the beach determine the formation of rip currents. They are currents that move perpendicular to the coastline in which the water flows from the shore towards.

Rip Currents What You Should Know

The sun, the sand, and the surf. But just because we're having fun, doesn't mean we can forget about safety. Get the facts about rip currents in this Ocean Today video. Rip currents are powerful, narrow channels of fast-moving water that are prevalent along the East, Gulf, and West coasts of the U.S., as well as along the shores of the Great Lakes.

What Causes A Rip Current? WorldAtlas

A rip current, is a narrow, powerful current of water running perpendicular to the beach, out into the ocean. These currents may extend 200 to 2,500 feet (61 to 762 m) lengthwise, but they are typically less than 30 feet (9 m) wide. Rip currents can move at a pretty good speed, often 5 miles per hour (8 kph) or faster. Rip Tides and Undertows

Rip Currents King Surf

A channel of churning/choppy water that is distinct from surrounding water A difference in water color, such as an area of muddy-appearing water (which occurs from sediment and sand being carried away from the beach). A consistent area of foam or seaweed being carried through the surf.

4 safety tips for summer weather hazards National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Rip currents may have velocities as great as 1 metre per second (3.3 feet per second, or 2 knots) and extend offshore from 60 to 760 metres (200 to 2,500 feet). The energies of the currents may be sufficient to erode shallow channels through offshore bars, and the water may be discoloured by suspended sand. Swimmers caught in a rip current.

NOAA Launches First National Rip Current Forecast Model

If you try to fight the rip current and swim against it, you'll just get worn out. Instead - float! If you're a good swimmer, swim parallel to shore until you've cleared the pull of the rip current. Swim with the waves, allowing them to push you to shore. If you can, wave and yell to get the attention of lifeguards and people on shore to let.

What is a rip current and how can you spot a one at the beach?

A rip current is a narrow, fast-moving channel of water that starts near the beach and extends offshore through the line of breaking waves. If you do get caught in a rip current, the best thing you can do is stay calm. It's not going to pull you underwater, it's just going to pull you away from shore. Call and wave for help.

Rip currents you've been warned Geological Digressions

Rip currents are a serious threat to beachgoers at any coast around the world. There are reported number of fatalities caused by rip currents every year in the U.S. and Australia. According to.

Rip Current Awareness Week — What you need to know Foremost Insurance Group

Vocabulary A rip current is a strong flow of water running from a beach back to the open ocean, sea, or lake. They can be more than 45 meters (150 feet) wide, but most are less than 9 meters (30 feet). They can move at 8 kilometers (5 miles) per hour. Rip currents are one of the most dangerous natural hazards in the world.

How to Spot A Rip Current

Rip current is named by Shepard and is present in almost all the seashores around the globe.Wind-stress pushes waves shoreward, and the water thus piled up moves alongshore till across-shore low stress allows it to return to the sea (Inman and Brush 1973; Smith and Largier 1995; Grant et al. 2005; Clarke et al. 2007; Reniers et al. 2009; MacMahan et al. 2010; Marchesiello et al. 2015).